John Bliss, 1795-1857, and his successors.

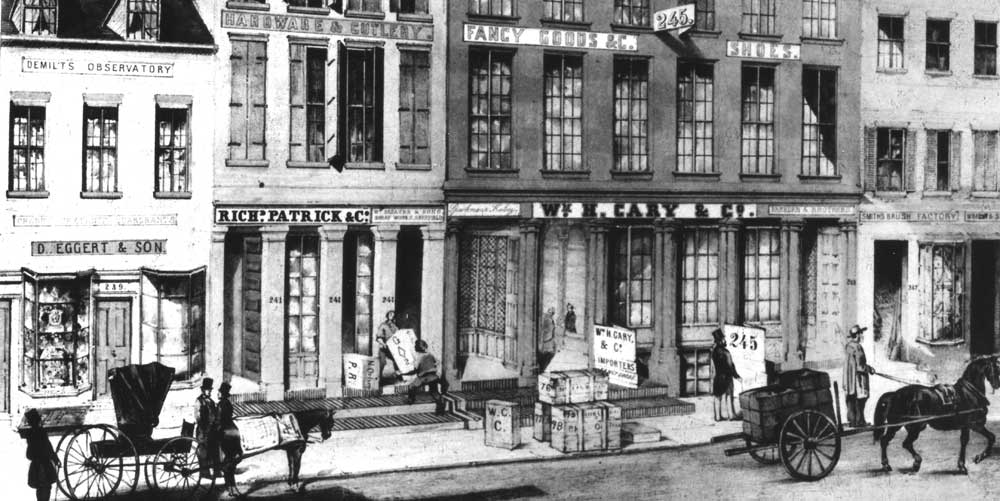

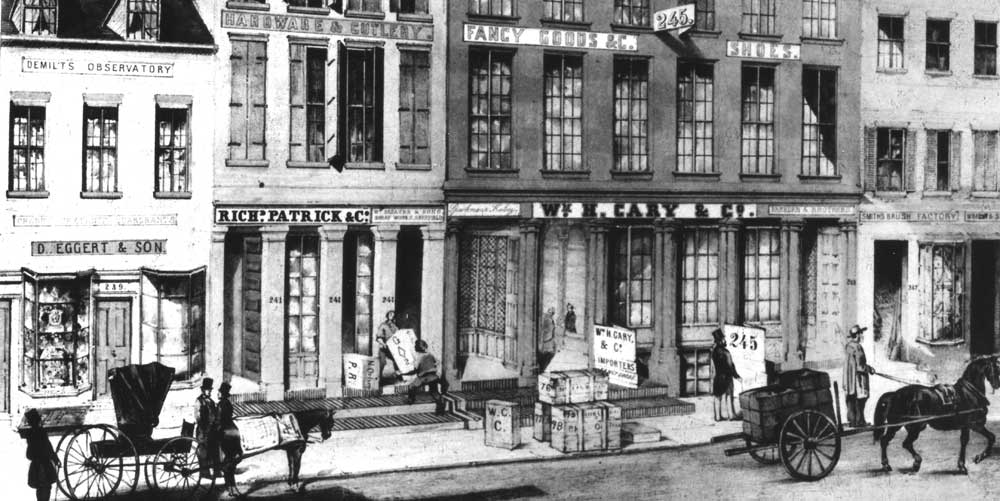

Pearl St. in New York City with (at left) the shop of chronometer makers D. Eggert & Son at 239 Pearl St. The Eggerts, competitors to the Bliss companies, were here between 1848 and 1874. The various locations of the Bliss companies would have been in buildings like these.

John Bliss (Sr.) was born July 15, 1795 (not 1775 as claimed by some writers) in Norwich Connecticut (the son of Zephaniah Bliss and Temperance Lord of Norwich, Ct.), and died in Brooklyn, New York on October 15, 1857. He was descended from Thomas Bliss who was born about 1590 in Gloucestershire, England, and died about 1650 in Hartford Ct. Thomas's father in England is the ancestor I have in common with John Bliss, so I'm only distantly related. I have been researching Bliss products & companies since I saw the Bliss items on display in the Nautical Instruments Shop at Mystic Seaport. James Bliss Marine of Boston was a completely separate company, although it was also founded in 1835. James Bliss was also descended from Thomas Bliss mentioned above but he and John Bliss are nearly as distantly related as I am to either.

John Bliss apprenticed to his uncle, silversmith and clockmaker Benjamin Lord in Rutland Vermont. Probably because of their incorrect birth date, both Charles Crossman ("A Complete History of Watch and Clockmaking in America") and Marvin Whitney ("The Ship's Chronometer") say Bliss apprenticed with Lord & [Nicholas] Goddard, but those gentlemen dissolved their partnership in April 1805, when John would only have been nine years old. According to the Genealogy of the Bliss Family in America (John Homer Bliss & Aaron Tyler Bliss) John Bliss married Abby Williams of Connecticut on September 19, 1830 at Canaan NY where his first child, John Bliss, Jr., was born on September 28, 1831. He and his family then resided at New Orleans, where son Samuel W. was born on June 12, 1833. Crossman and Whitney both say he began repairing chronometers while in New Orleans, and formed a partnership with a Mr. Whiteman, doing business as Bliss & Whiteman. I have not had an opportunity to research this company or John Bliss's stay in New Orleans. He and his family then returned to New York City, where he set up as a jeweler around 1835. He later resided in Brooklyn, NY, but maintained his business in lower Manhattan (he must have commuted by ferry, as the Brooklyn Bridge wasn't built until 1883). A daughter Sarah was born in Brooklyn on June 10 1835 (she died at age 2). His third son, George H., was born in Brooklyn July 18, 1838.

It is not currently known what John Bliss did between his apprenticeship with Benjamin Lord and his marriage in 1830. Crossman & Whitney say that after his apprenticeship, he went to New York City for a short while, and then traveled to Zanesville Ohio where he made clocks in partnership with Francis Cleveland, and then went to New Orleans. If so, he had to travel to Canaan New York (which is rather close to Rutland where he apprenticed) and then return to New Orleans again. Both Crossman & Whitney say he was in a partnership with Cleveland as clockmakers and silversmiths in Zanesville, but disagree on the dates. Crossman says they started in 1815 (when Bliss would have been 20), and Whitney says 1817. A history of Zanesville OH on the web says Cleveland's partner was "Captain John Bliss" and that he organized the Zanesville Artillery militia unit in 1818. This sounds more as if "Captain John Bliss" was a veteran of the war of 1812, and sufficiently well known in Zanesville to be trusted to run a militia company, unlikely for a 23-year-old newcomer. I strongly suspect Zanesville's Capt. John Bliss and our John Bliss are two different persons. There was in fact a Captain, later Major, John Bliss who was involved in the Indian Wars in the Midwest when our John Bliss was in business in New York. The Bliss family history was first published in 1880, and its information on this branch came from John Bliss's sons, so it's interesting there is no mention of John Bliss Sr. traveling to or working in Zanesville in it, or of any military connection. Of course, Crossman states his information about John Bliss also came from the sons. Whitney's account of John Bliss is obviously based on Crossman.

John Bliss was listed as a Jeweler at 180 Water St. in New York in 1835. Later that year he went into business with English watchmaker Frederick Creighton, as Bliss & Creighton (from Bliss & Co. Almanacs). They set up initially as jewelers & silversmiths at 42 Fulton St., in lower Manhattan, near the South Street docks, apparently taking over the business of Clement Davison (see p. 131 of Bailey, Two Hundred Years of American Clocks & Watches, and below). The Bliss companies remained in this general area for their entire existence. The picture above of the D. Eggert & Son shop on Pearl St. is typical of the area. My coin silver spoon marked "BLISS & CREIGHTON" surely dates from this time. They also sold pocket chronometers with their name on them. These were high quality fusee watches with detent escapements. Bliss & Creighton were certainly capable of making them, but it's just as possible these were English made "contract" watches. Although possibly sold for gentlemen's use, these were probably intended as 'comparing watches' used to time navigational sights then compare the time with the ship's chronometer which was kept safely below decks. One was pictured in the Feb. 2002 NAWCC Bulletin. I have seen an early Bliss & Creighton watch paper that says:

* WATCHES, CLOCKS, SILVER WARE, JEWELRY &C, &C *

BLISS & CREIGHTON

WATCH MAKERS

Sucessors to

C. DAVISON

42 FULTON ST.

2nd Store above Pearl

NEW * YORK

CHRONOMETERS REPAIRED & RATED BY TRANSITS.

Almost certainly John Bliss and Frederick Creighton had the manufacture of chronometers in mind when they became partners in 1835. Chronometers are very accurate portable timekeepers developed around 1780 which until recently were essential for navigation at sea. By 1839 they were in production; in 1840 they had submitted nos. 501 and 506 for trial at the Naval Observatory in Washington D.C. I suspect that no. 501 is the earliest serial number for a Bliss chronometer as I have not seen any lower. As noted by Whitney, chronometer makers never started with 0, as who would buy something that was obviously a maker's first attempt? It should also be noted that once made, chronometers took several months to several years to settle down to a regular rate so they weren't sold fresh off the bench. Nos. 501 & 506 apparently didn't meet Observatory standards, supporting my view they were among the first produced by Bliss & Creighton. In the beginning they used rough parts made in England but by 1848 they had outfitted their workshop with the machinery needed to make all parts themselves, and then advertised that their chronometers were entirely American made. I believe they were the second company to make chronometers completely in America, William Bond and Son of Boston being the first in 1812. Bond's first chronometer is in the Smithsonian and their chronometer shop is on display there (at least it was when I last visited). Bliss & Creighton was one of the very few American companies capable of making chronometers completely from scratch. John Bliss & Co. later claimed they were the only company able to do this, but it's pretty certain T.S. & J.D. Negus, and perhaps others, also could make chronometers completely in America.

Bliss & Creighton chose an excellent time to enter the chronometer market. Although the basic design of ship's chronometers had been settled by 1780, they were expensive and the maritime community was not convinced of their reliability. While both the Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy issued chronometers to ships engaging in long voyages or voyages of exploration, it wasn't until around 1835 that they began regularly issuing chronometers to most ocean-going vessels. By 1835, the merchant marine community had been similarly convinced of the reliability and economic desirability of chronometers, so there was a great demand. By the 1850s, this demand had lessened greatly. This reduction in demand was, I'm sure, a major factor in the company's dissolution in 1853. A problem for all chronometer makers at the time was the quality of the instruments they built. If reasonably well cared for, they lasted far longer than the ships on which they were used. Chronometers made in the mid 1800's were in demand for use on WWII Navy and merchant marine ships, where they performed very well. My John Bliss & Son chronometer from c. 1855 has obvious signs of WWII use.

In 1845 Bliss & Creighton patented a new design (U.S. Patent no. 4135 dated Aug. 4, 1845) for a chronometer balance wheel to correct for the middle temperature error that plagued chronometer makers. Middle temperature error is the tendency for a chronometer with an Earnshaw or Z-shaped balance to run several seconds a day faster when the temperature is around 70 degrees F. compared to its performance at 40 degrees or 90 degrees. John Bliss & Son and John Bliss & Co. continued to produce chronometers with this patented balance wheel at least until the patent expired in 1862. Creighton & Black, also successors to Bliss & Creighton, used the patent balance on their (apparently) limited production of chronometers. It should be noted that this patent puts Bliss & Creighton in the forefront of chronometer development. The London maker John Poole invented his well-known "Poole's Auxiliary" compensation in the same year (although it had been independently invented & used by earlier English makers). Although the noted chronometer historian Rupert T. Gould spent a good portion of his landmark The Marine Chronometer on auxiliary compensation for middle temperature error, he doesn't mention the Bliss & Creighton patent at all. Middle temperature correction continued to be a subject of development by the Bliss companies; the chronometers shown at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition had an auxiliary invented by John Bliss & Co., although as far as I can tell it was never patented and is only described in the Bliss Almanacs. John Bliss & Co. was also awarded US Patent no. 492,184 in 1893 for an auxiliary compensation. They also appear to have used Hartnup's Auxiliary. At some point after 1900, they seem to have settled on palladium balance springs for their commercial chronometers, and only used steel springs for Navy chronometers, as the Navy wouldn't accept anything else. Later on, the celebrated John Bliss & Co. chronometer craftsman Arthur C. Fox assembled a "fine and rare" collection of auxiliary balance compensation devices, which probably came from chronometers that had their balances replaced with palladium or invar/elinvar combinations.

Bliss & Creighton dissolved their partnership acrimoniously in 1853. Crossman states "The firm then dissolved owing to some dissatisfaction on the part of Mr. Creighton. . . . There was, however, some difficulty in the division of the business and a receiver was appointed, the final outcome being a long and tedious lawsuit, which was not settled until after the death of both participants." John Bliss then took his oldest son, John Jr., into partnership, establishing the firm of John Bliss & Son at 40 Fulton St., then at 26 Burling Slip. Frederick Creighton formed a partnership with Garret C. Black, a former employee of Bliss & Creighton, and continued to do business at the 42 Fulton St. address as Creighton & Black. John Bliss Sr. died on October 11, 1857, age 62, and Frederick Creighton died one week later.

When the elder John Bliss died, his son John Jr. established John Bliss & Company with his middle brother, Samuel, as partner (Whitney says it was with George, but the Jeweler's Circular says otherwise). According to the Jeweler's Circular, v78, no. 1 (1919), Samuel retired from the firm in 1864 (strange, as he was only 31) and the youngest brother, George H., then became a partner. When George died Aug. 5, 1897, age 59, John Jr. took his son John Lord Bliss as a partner. John Jr. died in 1903 at age 72, and his son John Lord Bliss continued to run the business until his death on Aug. 23, 1927, at age 70. John Lord Bliss was survived by two daughters, Natalie and Ruth Wyllys Bliss. I don't know what happened to the business after his death.

Interestingly, most of the patents after 1867 that I've found were issued either to John Jr. and his brother George, or later just to John Lord Bliss. Samuel never appears as a patentee, but in 1870 he did sign the application for patent no. 103,417, a tripod for a watchmaker's transit, as a witnesses. See the table below for the various locations of John Bliss & Co.

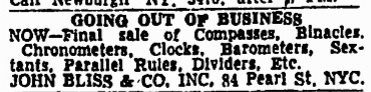

John Bliss & Co. went out of business in 1956, when the building at 84 Pearl St., where their store had been located from 1929, was sold, and they couldn't find suitable premises elsewhere. This classified ad appeared in the New York Times dated Aug. 19, 1956:

|

Our predecessors, Messrs. Bliss & Creighton, established in 1835, to whom a Gold Medal was awarded at a Fair of the American Institute as early as 1848, and ourselves, have been the only makers of Marine Chronometers in which all the parts were of American Manufacture. The machinery and special tools employed have continued in our possession, and, together with the addition of some excellent modern wheel and pinion cutting engines, constitute our present facilities. We have manufactured many chronometers from Lancashire movements, for convenience only, while this has been, and is, the invariable practice of all other American makers.

ABRIDGMENT (sic) OF THE NAUTICAL ALMANAC AND TIDE TABLES 1878 and later |

This was part of the description of John Bliss & Co.'s participation in the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, where a number of their chronometers were on display. Four of these were chosen at random and subjected to trial. All Bliss chronometers displayed at the Exhibition were entirely made in America by Bliss, and the quality of workmanship and performance earned them a medal for "Excellence of workmanship, and great skill in the adjustment of Marine Chronometers for both temperature and isochronism." The picture below is of a display showing all parts of a chronometer in various states of completion, demonstrating that John Bliss & Co. could make all the parts themselves. This was made for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition (over the years a complete balance wheel and a dial were 'commandeered'; their shadows remain on the felt backing). This display can be seen in Mystic Seaport Museum's Nautical Instruments Shop. Click on the image to zoom in.

The mention above of Lancashire movements refers to the practice of buying rough movements, called ebauches (pronounced 'e-bosh'), from cottage makers in Lancashire, England. These movements included the basic wheelwork and plates; the manufacturers added the detent, balance wheel and escapement, and then adjusted all to chronometer standards. Not only was this done by American makers, it was also done by the great English makers as well. The craftsmen employed by chronometer manufacturers were highly paid, and it was cheaper to have lower paid Lancastrian clockmakers do the basic work and let the chronometer makers concentrate on what they did best (most Swiss watches are still made this way). It wasn't until around 1907 that the great English maker Mercer brought all aspects of chronometer production into their shop.

Bliss & Creighton and the later Bliss companies sold all the items needed for navigation, including charts, quadrants & octants, logs, etc, as well as their chronometers. In 1871 John Bliss & Co. acquired the stock of Blunt & Co. when the owner(s) retired from the nautical business. Blunt made sextants and octants, and were particularly known for publishing charts and useful nautical books. John Bliss & Co. also made compasses, taffrail logs, and surveying instruments with their own patents. I believe the Bliss taffrail log, first patented in 1864, was the first successful taffrail log. It was invented by Capt. Truman Hotchkiss of Stratford, CT. John Bliss & Co. acquired his patents, and continued to improve the log with their own patents.

Apparently due to a declining demand for chronometers and decreasing support from the Navy, sometime around the turn of the 20th Century John Bliss & Co. ceased making their own chronometers, and began importing complete instruments made for them by Victor Kullberg of London. This occurred before SN 2972, which is the earliest Kullberg movement I've recorded. Kullberg movements can be identified by the position of the winding arbor (winding key post) as Kullberg used a reverse fusee. If you look at my chronometer movement pictures, you'll note that if the balance wheel is closest to you, the winding arbor is on the left on both the Bliss & Creighton and the John Bliss & Son, while it is on the right on the John Bliss & Co. instrument. Bliss/Kullberg movements all appear to have a regular Earnshaw movement, probably due to the fact that the U.S. Navy had decided it would no longer accept chronometers with auxiliary compensations because they were so difficult to keep in adjustment. Despite this, Bliss continued to experiment with temperature correction. A number of their later chronometers used palladium rather than steel hairsprings. These are white in color, are not affected by magnetism, and aren't subject to rusting. Palladium springs are much less sensitive to temperature and with proper balance design they effectively eliminate middle temperature error. They were softer than steel springs so were more difficult to make and didn't keep their shape as well, so the Navy wouldn't accept them either. I have seen a Bliss/Kullberg chronometer less than 20 numbers earlier than mine with a palladium spring. Mine has a steel spring, which is probably due to its having been purchased by the Navy. Bliss also experimented with invar balances, which are not affected by temperature either. I have seen one very late Bliss chronometer that is not a Kullberg; most likely it's a Mercer.

John Bliss & Co. began producing a number of nautical instruments themselves, namely compasses, binnacles, logs, azimuth (bearing) instruments, and transit instruments. In addition they sold sextants made in England and later Germany with their name on them, as well as other nautical items such as rules, binoculars, barometers, and Chelsea clocks that were made by others but with John Bliss & Co. on them. The barometers, telescopes and binoculars were made in France. According to Chelsea Clock Co. records, the first Chelsea ship's clock was sold to John Bliss & Co. Bliss/Chelsea clocks could say just "JOHN BLISS & CO. NEW YORK" on the dial, or they could also have "CHELSEA BOSTON" on them. Chelsea made barometers to match their ships clocks, so you could get a clock and barometer set labeled for Bliss. The French-made Bliss barometers were just as good, and I assume they were cheaper.

The earliest mention of Bliss compasses I've seen is in the 1877 Almanac. This lists dry card compasses in sizes from 4.5 inches to 6.5 inches; the illustration shows that the card has the standard fleur-de-lis for North, and has a plain East point. Since I've seen a Bliss dry card compass with a cross in the East point, I gather they started making these compasses much earlier. The cross indicated the direction to the Holy Land, and its use fell out of favor after the Civil War. The dry card compasses could be had in wood or brass bowls, and in tell tale configuration. A tell tale compass is designed to be mounted on the overhead (ceiling) so the captain could check on the helmsman's steering, hence "tell tale".

The Ritchie company of Massachusetts (still in business) invented an improved liquid-filled compass in the 1860s. Although John & George Bliss took out several patents for improvements to liquid compasses in 1870, no such compasses were listed in the 1877, 1878, or 1888 catalogs. The earliest mention of Bliss liquid compasses I've seen is in the 1893 Almanac, and it appears to be an announcement of a new product, so I believe production of Bliss liquid compasses began around 1892. It appears to have continued to after World War II, as I've seen several late serial number compasses that more closely resemble standard Navy compasses than typical Bliss compasses. Also, I have never seen a Bliss liquid compass that utilizes the 1870 patents. While John Jr. and George took out the compass patents, John Jr.'s son John Lord Bliss became an expert compass adjuster. In addition to being completely familiar with Lord Kelvin's binnacles and compass adjustment system, John L. Bliss patented several improvements to binnacles himself. A binnacle is a housing that holds a ship's steering compass and has several means of adjusting that compass. Adjusting a ship's steering compass involved counteracting as far as possible the affect of a ship's magnetic field on it's steering compass, so that the compass could accurately respond to the Earth's magnetic field. Careful builders and captains of wooden ships made sure there were no magnetic objects near the compass, but with the advent steam engines, and then of iron and steel ships, more effective compensation was needed, and Lord Kelvin provided it with his binnacles.

See my log page for a complete treatment of these. I believe the first Bliss log was produced between 1867 and 1878, and was the first taffrail log commercially produced. It was based on patents issued in 1864 and 1867 to Captain Truman Hotchkiss of Stratford Connecticut. A taffrail log is a patent device that displays the distance traveled on a register attached to the taffrail at the vessel's stern. It allows a continuous determination of distance without the necessity of either casting the chip log or hauling in the older style one-piece patent log. These logs were very popular and continued to be made at least into the 1930s. Bliss developed several other log designs, but the original appears to have been by far the most popular. It was copied (one assumes after the relevant patents expired) with one change by the John Hand Company of Philadelphia.

As mentioned elsewhere, I am not a direct descendent of the family members who founded and operated these companies. I have no company records, nor do I know if any records survive.

Because information about Bliss chronometers, including serial numbers and dates, has appeared in many publications, I can roughly date them. No such information exists for compasses, even though the Bliss liquid compasses have serial numbers. I do believe that production of liquid compasses began around 1892, and ended after WWII. The highest compass SN I've seen is just over 6500, purchased in 1948.Bliss "American" logs have no serial numbers. The two or three digit number stamped on the end cap is not a serial number; perhaps it is a batch number. My Mark II log does have a serial number. The only way to date Bliss logs is by the patent numbers, or lack thereof, on them. Until recently, patents lasted 17 years. See my log page for more details on the patents. Obviously no instrument could have been made before the latest patent date, and I feel it wouldn't have been made later than 17 years after the last date.

Similarly, I cannot tell you to whom any instrument was sold, or where or how it was used. As with any antique, your best source is to trace the chain of ownership back, starting with how you acquired the item.

Books & articles published by, or containing information about the Bliss Companies:

Abridgment of the Nautical Almanac and Tide Tables (title varies). Published yearly by Bliss & Creighton, John Bliss & Son, and John Bliss & Co. Also catalogs published by the companies.

Bailey, Chris. Two Hundred Years of American Clocks & Watches. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

Bedini, Silvio A. Thinkers and Tinkers: Early American Men of Science. Rancho Cordova, CA: Landmark Enterprises, 1983. Facsimile of book originally published in 1975 by Charles Scribner's Sons.

Bliss, Aaron Tyler. Genealogy of the Bliss Family in America. Midland, MI: published by the author, 1982. "Including the compilations of Judge Oliver Bliss Morris, of Springfield, Massachusetts, Sylvester Bliss, Esq., of Boston, Massachusetts, and John Homer Bliss of Norwich and Plainfield, Connecticut. Being a corrective reprint and revision of the latter's book which was published in 1881, and also an update through the year of 1981."

Brewington, M.V. The Peabody Museum Collection of Navigating Instruments With Notes on their Makers. Salem, MA: Peabody Museum, 1963 (reprinted by Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, MA, and Maurizio Martino Publisher, Staten Island, NY).

Carlisle, Lilian Baker. Vermont Clock and Watchmakers, Silversmiths, and Jewelers 1778-1878. Burlington, Vt. [Distributed by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vt.], 1970. Information about Benjamin Lord. John Bliss, who I believe was his nephew, apprenticed with him.

Cooper, David. John Cairns (1751-1809) and Other Early American Watchmakers. NAWCC Bulletin, National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, Columbia, PA. No. 336, Feb. 2002, p. 26.

Crossman, Charles S. A Complete History of Watch and Clock Making in America. Compiled and edited by Donald L. Dawes. Published privately by Donald L. Dawes, 2002, second printing 2006. This is a compilation of Crossman's articles that appeared in the Jeweler's Circular and Horological Review in 1886, '87, '88, '89, '90 and 1891. This appears to be the source of much of Whitney's history of John Bliss (including the incorrect birth date).

De Fazio, Thomas L. Notes On The Bliss & Creighton Chronometer Patent, Antiquarian Horology, Antiquarian Horological Society London, No. 4, Vol. 10, Autumn 1977, p. 427.

Mercer, Tony. Chronometer Makers of the World. Colchester, Essex, England: N.A.G. Press, 1991.

Milham, Willis I., Ph.D. Time & Timekeepers. New York: The Macmillan Co., 1944.

NAWCC Bulletin, various issues, members can check an online index at nawcc.org. Published by the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, Columbia, PA.

Norwich Town Records, now kept at the Connecticut State Library, Hartford Ct, confirmed John Bliss's date of birth (1795).

Patterson, Howard (Capt.). Hand Book to the U.S. Local Marine Board Examination for Masters and Mates of Ocean-Going Steamships. New York: John Bliss & Co., 1890, 1897.

Sturdy, E.W. (Lieut.). A Practical Aid to the Navigator. New York: John Bliss & Co., 1884.

Thoms, William (Capt.) A New Treatise on the Practice of Navigation at Sea. New York: John Bliss & Co. 1890.

Whitney, Marvin E. The Ship's Chronometer. Cincinnati, Ohio: American Watchmaker's Institute Press, 1985, 1991.

Whitney, Marvin E. Military Timepieces. Cincinnati, Ohio: American Watchmaker's Institute Press, 1992.

Books about Maritime instruments in general:

Andrewes, William J.H. (ed). The Quest for Longitude. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1996. Proceedings of the Longitude Symposium at Harvard, November 1993.

Bedini, Silvio A. Early American Scientific Instruments and their Makers. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1964.

Cotter, Charles H. A History of the Navigator's Sextant. Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1983.

Gould, Rupert T. The Marine Chronometer: Its History and Development. London: The Holland Press, 1923 (reprinted 1960, 1971, 1973). The pre-eminent book about mechanical chronometers, but very dated. Nothing about American makers or inventions. About to be reprinted in England.

Gurney, Alan. Compass: A Story of Exploration and Innovation. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004. Excellent and informative history of the marine compass.

May, W.E., Commander. A History of Marine Navigation. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973. Includes a chapter on Modern (WWII to 1973) Developments by Capt. Leonard Holder.

Morris, W.J.. The Nautical Sextant. Arcata CA: Paradise Cay Publications, Inc. & Wichita KS: Celestaire, Inc., 2010.

Randier, Jean. Marine Navigational Instruments. London: John Murray, 1980. Translated from the French by John E. Powell.

Randier, Jean. Nautical Antiques for the Collector. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1977.

Sobel, Dava, and William J. H. Andrewes. The Illustrated Longitude. New York: Walker and Company, 1998. Illustrated edition of Sobel's bestseller Longitude about John Harrison and the quest for longitude at sea. Unlike the original book, this is copiously illustrated, with additional material by Andrewes.

Turner, Gerard L'E. Antique Scientific Instruments.

Poole, England: Blanford Press Ltd, 1980.

Created 6/9/02

Modified 1/11/12